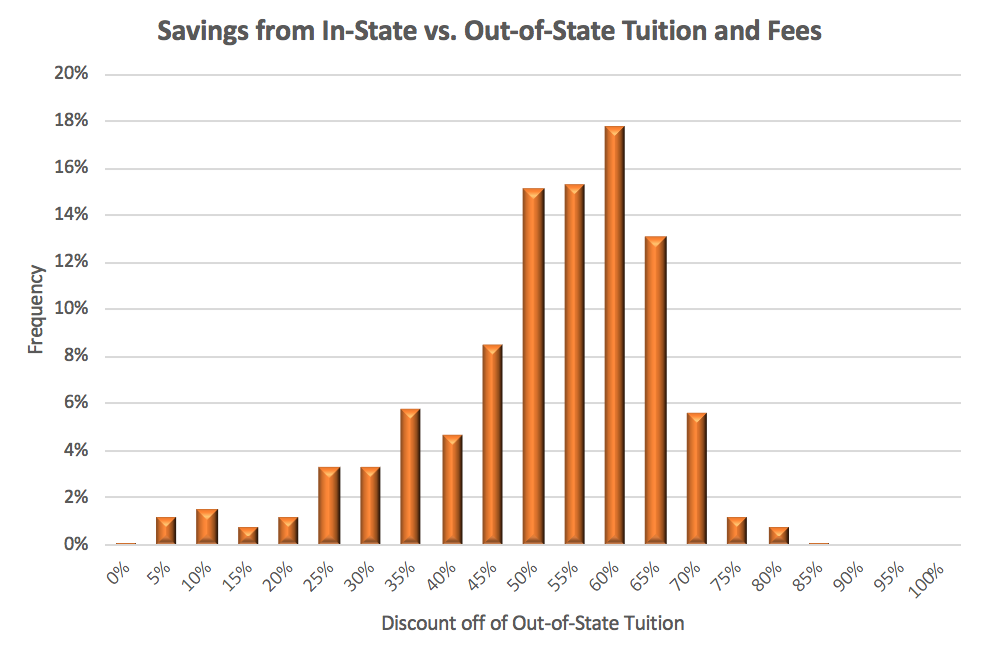

Public colleges charge lower in-state tuition rates for state residents, typically saving them one-third to two-thirds off out-of-state tuition.

The out-of-state tuition rates charged to non-residents are thousands of dollars to tens of thousands of dollars more expensive. This gives out-of-state students a strong financial incentive to try to qualify for in-state tuition.

State Policies for In-State Tuition

Each state has different requirements for determining whether a student qualifies for in-state tuition. Rules are set by the state legislature, the state board of regents, or the state board of higher education but implemented by each college. Typically, the college’s registrar determines whether a student qualifies as a state resident for in-state tuition purposes. There may also be policies that allow out-of-state students who are not state residents to qualify for in-state tuition.

Policies concerning eligibility for in-state tuition typically involve two requirements.

- Purpose. The primary purpose for moving to the state must have been for a reason other than qualifying for in-state tuition rates.

- Duration. The student (and the student’s family, if the student is a dependent student) must have been a state resident for at least at least a minimum period of time.

States have long lists of criteria for evaluating a student’s reason for relocating to the state is not just to save on college tuition. They want to be sure the student genuinely wants to become a long-term state resident.

Most states require the student to provide clear and convincing evidence that they have established a permanent domicile (a permanent home, not just temporary residence) in the state. This is a stronger evidentiary standard than a preponderance of evidence.

The durational requirements may be waived in certain circumstances, such as for members of the U.S. Armed Forces.

Purpose

The reason for moving to the state must be for reasons other than education.

The student must present clear and convincing evidence that they moved to the state for a reason other than qualifying for in-state tuition and that they intend to make the state their permanent home.

The most common reason for moving to a state is to obtain full-time permanent employment in the state or because of a job transfer. Documentation of employment in the state can include:

- Pay stubs or a military Leave and Earnings Statement (LES) with a residential address in the state

- A statement from the employer on letterhead showing the dates of employment in the state

Another possible reason for moving to a state is to acquire or establish a business in the state. Evidence of this can include:

- Proof of ownership of a business located in the state

- Copy of a corporate income tax return with a state address

- Obtaining a license for conducting a business in the state

- Acquisition of commercial real estate in the state

See also: Complete Guide to Financial Aid and FAFSA

State Residence and Domicile

The student must also provide proof of state residence and domicile. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, a domicile is a person’s permanent home and a residence is a temporary home. A person can have multiple residences but only one domicile. People pay taxes and vote based on the location in which they are domiciled. Eligibility for in-state tuition is based on domicile, not residence.

No single type of evidence is considered conclusive proof of in-state residence and domicile.

Primary factors for determining eligibility for in-state tuition include the following, which demonstrate intent to establish domicile in the state and which provide a non-educational purpose for changing domicile. These factors provide the strongest evidence of eligibility for in-state tuition.

- Full-time employment in the state

- Owning and operating a business in the state

- Obtaining a state professional or occupational license

- Marriage to a state resident

- Significant reliance on state sources for financial support

- Ownership of a home in the state, as evidence by a mortgage and/or deed

- Presence in the state during periods when not enrolled as a student

- Attendance and graduation from a secondary school in the state immediately prior to college enrollment

- Filing federal and state income tax returns with a state residential address, as evidenced by copies of income tax returns, W-2s and 1099s with a state residential address

- Obtaining a state driver’s license or state-issued photo ID

Secondary factors for demonstrating eligibility for in-state tuition include the following, which are of a less permanent nature. These factors, on their own, are usually not enough to demonstrate eligibility for in-state tuition, but they can support a claim that the student is a state resident.

- Signing a declaration of domicile in the state, revoking residency in any other state

- Registering to vote in the state and voting in the state as a state resident

- Registering a car in the state and obtaining auto insurance in the state

- Rental of an apartment in the state

- Utility bills with a state residential address

- Transferring all checking and savings accounts and safety deposit boxes to the state

- Registering with Selective Service in the state

- Part-time employment in the state

- Obtaining state hunting and fishing licenses

- Credit card bills with a residential address in the state

- Participating in religious, professional, civic, social and volunteer organizations in the state

- Obtaining and using a local library card

- Evidence of family ties to the state

The student should also sever connections with other states, by making sure few, if any, of the primary or secondary factors apply to a different state. If the student maintains connections with another state or claims residence in another state, it can prevent them from demonstrating residence in the new state.

Durational Requirements

Most states require the student to have been a state resident and physically present for at least one year (12 consecutive months consisting of 365 days) prior to initial enrollment or registration.

There are a few exceptions:

- Alaska requires 2 years

- Arkansas requires 6 months

- Illinois and Minnesota require a full calendar year

- Massachusetts requires 12 months for colleges and universities and 6 months for community colleges

- Nebraska requires 12 months for independent students, but no minimum period of residence for a dependent student’s parents

In all states, the period of residency must be continuous, without breaks.

Most states define the period as ending on the date of initial college enrollment or registration, usually the first day of the academic term or semester. Alaska, Maryland and Texas base it on the census date or add/drop date of the term. Minnesota bases it on the date the student applied for admission. Tennessee bases it on the date the student is admitted. California and Hawaii base it on the residency determination date.

North Dakota also allows former state residents who were domiciled in the state for 3 consecutive years within 6 years of enrollment to qualify for in-state tuition.

Time enrolled in a state college or university does not count towards satisfaction of the durational requirements, even if the student moved to the state for other than educational purposes.

Dependent vs. Independent Student Status

Students are considered to be either dependent or independent. This is not the same as dependency status on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). But, dependency status for determining whether the student is a state resident does depend on the sources of financial support to the student and the age of the student.

The state residency of a dependent student is based on the state residency of the student’s parent or legal guardian. If a dependent student’s parents are divorced or separated, the student’s state residency may be based on the state residency of either parent. Some states limit this to the parent who has legal custody of the student.

A legal guardianship must not have been established for the sole or main purpose of qualifying the student for in-state tuition.

Financial Support

If a student’s parent or legal guardian provides financial support to the student, the student is generally considered to be a dependent student for state residency purposes.

If the student can be claimed as a dependent on someone else’s tax return (other than a spouse), they are considered to be a dependent student for state residency purposes. Note that this test is based on whether the student can be claimed and not whether the student is actually claimed on someone else’s federal income tax return.

In Utah, if the student can be claimed on the income tax return of a non-resident, the student is ineligible for in-state tuition.

Some states will look back two or three years when determining whether the student is financially dependent on their parents or other relatives, even if the durational requirement for state residency is only one year.

To be considered an independent student, the student must not receive more than a specified amount of financial support from their parents or legal guardians. In most states, the student must provide more than half of their own support. California limits the student to receiving at most $750 per year from their parents in the current and three previous years. In some states, receiving any financial support from out-of-state disqualifies the student for in-state tuition.

Financial support includes not just the direct payment of money. It can include receiving student loans that were cosigned by a parent or other relative. It can include in-kind support, such as a parent paying the insurance premiums on the student’s car or providing the student with cell phone service. A trust that was established or controlled by a relative is considered financial support from that relative and demonstrates a lack of financial independence.

Student Age

The student must also have reached the age of majority for the state or have court-ordered emancipated minor status to be considered an independent student. Some states have a higher minimum age requirement for a student to be considered independent.

- Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Mexico, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Utah and Vermont require the student to be at least 18 years old.

- Alabama and Nebraska require the student to be at least 19 years old.

- Illinois, Indiana, Mississippi and Missouri require the student to be at least 21 years old. Colorado requires the student to be at least 22 years old.

- Arkansas requires the student to be at least 23 years old.

- California, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Virginia and Wyoming require the student to be at least 24 years old.

Some states will allow students who have not yet reached the required minimum age to be considered independent if they are married, a graduate student or satisfy the requirements for independent student status on the FAFSA.

If the student’s parent(s) move out of state, some states allow the student to retain state residency for a continuous period of enrollment. Other states allow the student to retain state residency for a limited period of time.

Lack of Negative Evidence

Most states require a lack of negative evidence that indicates ongoing ties to another state. Negative evidence includes:

- Maintaining a home in another state

- Claiming a credit on the state tax return for income taxes paid to another state

- Maintaining bank accounts in another state

- Voting in another state

- Retaining auto registration in another state

- Receiving public assistance from another state

- Filing a declaration of domicile in another state

- Admissions records that are inconsistent with state residence, such as listing an out-of-state address on an application for admission

Any act inconsistent with being a state resident will cause the request for resident tuition to be denied.

Treatment of Undocumented Students and Parents

The rules concerning state residency for in-state tuition cannot consider whether a student’s parents are undocumented. If the student is a U.S. citizen and they satisfy the other requirements for in-state tuition, they are eligible for in-state tuition even if their parents are undocumented or foreigners.

Some states provide in-state tuition for undocumented students who are state residents. They work around the limitations of federal immigration law by basing eligibility for in-state tuition on whether the student graduated from a state high school, as opposed to state residence.

Exemptions to the Durational Requirements

Many states provide a few exemptions to the durational requirements, such as for members and veterans of the U.S. Armed Forces and their dependents, public college faculty and staff, public school teachers and marriage to a state resident. In addition to these criteria, there are also several unusual criteria for in-state tuition.

Military Exception

All states provide an exception to state residency requirements for members of the U.S. Armed Forces, their spouses and dependent children.

The member of the military must either be stationed in the state or have a home of record in the state. A copy of form DD-2058 may be required to verify the servicemember’s military state of legal residence.

If the home of record is in the state, the Servicemember may be required to file state income tax returns as a state resident.

Some states include members of the National Guard and Reserves within the scope of the military exception, some do not. Such states include Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, Washington and Wisconsin. Some require a minimum length of service, such as 2 years, which is longer than the durational requirement for residing in the state.

Arkansas and Oklahoma include ROTC scholarship recipients who have executed a U.S. Armed Forces service contract within the scope of the military exception.

Civilian employees of the military are not eligible.

Veterans Exception

Section 702 of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Choice Act) requires public colleges to provide in-state tuition to veterans and their dependents, effective for terms starting on or after July 1, 2015. If the college charges veterans and their dependents higher tuition and fees than for state residents, the college is ineligible for the Montgomery G.I. Bill-Active Duty and Post-9/11 G.I. Bill.

This law applies to veterans and their dependents (spouse and dependent children) who live in the state, even if their legal residence is in another state. The veteran’s dependents must use transferred veterans’ education benefits or the Marine Gunnery Sergeant John David Fry Scholarship to pay for the college. In all cases the student must enroll within three years of the veteran’s discharge or death in the line of duty after a period of active duty service of 90 or more days. Once enrolled, the student retains eligibility for in-state tuition so long as they remain continuously enrolled in the college, even if the 3-year enrollment window has ended.

Dependents include the veteran’s spouse and dependent children. Spouses include same-sex spouses. Children include biological and adopted children, as well as stepchildren.

First Responder Exception

Alabama, Alaska, California, Georgia, Maine, Michigan, North Dakota, Tennessee and Wisconsin provide a tuition waiver for the spouse and dependent children of first responders (police, fire and EMT) who were killed in action. Tennessee and Wisconsin also provide a waiver for total and permanent disability. Eligibility for the tuition waivers may be means tested.

University Employee Exception

Several states provide a state residency exception for employees of the public university system, their spouses and dependent children. Most require full-time employment, but some allow less than full-time employment to qualify.

States with such an exception include Alabama, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Carolina and Washington.

Some states limit the exception to the college or university where the employee is employed. Some may provide additional tuition discounts for employees, their spouses and dependents. There may be reciprocity agreements with other colleges, including out-of-state colleges.

Generally, graduate student teaching and research assistants are not eligible, nor are medical residents, interns and fellows. However, Minnesota, Mississippi and New Mexico allow graduate students holding assistantships to qualify for in-state tuition.

Similar rules may also apply to public elementary and secondary school teachers and administrative staff, depending on the state. Such states include Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois and Nevada.

Full-Time Employment

Some states will waive the durational requirement if the student’s parent or spouse got a full-time permanent job in the state. These states include Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Tennessee.

Connecticut and Wisconsin reduce the durational requirement from 12 months to 6 months.

California provides in-state tuition to the spouse and dependent children of full-time employees of any state agency.

Florida provides in-state tuition to full-time employees of state agencies and political subdivisions when the state agency or subdivision pays the cost, but only for job-related law enforcement and corrections training.

A student who is a migrant farmworker or whose parent is a migrant farmworker may qualify for in-state tuition even though they do not continuously reside in the state. Typically, they must have been a migrant farmworker who worked in the state for two years prior to enrollment.

Some states will allow a student to qualify for in-state tuition if their parents moved to the state for retirement purposes. The parents must provide evidence of retirement, such as receipt of Social Security retirement benefits.

Marriage

Marriage to a state resident exempts the student from the durational requirement if the spouse already satisfies the state residency requirements in some states. These states include Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas and Washington.

Marriage to a state resident does not automatically convey eligibility for in-state tuition in Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina. Eligibility for in-state tuition is determined separately for each spouse, although marriage to a state resident is a factor that can be considered as evidence of intent to make a permanent home in the state.

Legacies

Louisiana and Mississippi waive the durational requirement if the student enrolls in a college from which their parent previously graduated. Children of graduates of the University of Alaska are eligible for in-state tuition.

Scholarship Recipients

Recipients of certain scholarships may be able to qualify for in-state tuition.

- Olympic athletes in California, Colorado and Utah. California athletes must participate in the U.S. Olympic Training Center. Time spent in training counts toward the one-year time period for Olympic athletes in Utah.

- Athletes receiving an athletic scholarship from a public college in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and New Mexico may qualify for in-state tuition. In some cases the athletic scholarship must equal or exceed the in-state tuition.

- Recipients of band and choral scholarships in Mississippi may qualify for in-state tuition.

- Recipients of tuition waiver scholarships for participation in campus performance-based programs may qualify for in-state tuition in Tennessee.

Admission to a college’s honors program may qualify the student for in-state tuition. For example, students who are designated a UA Scholar at the University of Alaska may qualify for in-state tuition. In Tennessee, each college sets its own policies regarding in-state tuition for students admitted to honors programs.

529 Plan Participation

Some states provide in-state tuition to 529 college savings plan participants even if they do not currently live in the state.

- Alaska 529

- KY Saves 529 – Beneficiary must have previously resided in Kentucky and must have at least 8 years of program participation

- My529 – Beneficiary must have previously lived in Utah and must have owned a my529 plan account for at least 8 consecutive years prior to May 5, 2008

Appeals Process

Every state has an appeals process whereby the student can appeal an adverse decision. An appeal is more likely to be successful if it includes new information that was not provided with the original application. If there was a specific deficiency in the original application, the appeal should address it. Students can appeal at most once per academic term.

Change in Residency Status

Even if the student is classified as a non-resident the during the first year, they may apply for a change in residency status in subsequent years, if their circumstances change.

The most common example involves a parent moving to the state for a job and becoming a state resident.

A student who graduates with an Associate’s degree or more advanced degree from a Louisiana college or university may qualify for in-state tuition for subsequent enrollment at the same college or university.