Borrowing too much money for college can cause delays in major life-cycle events, such as buying a car, getting married, having children, buying a home and saving for retirement. Student loan payments may divert funds that could be used to achieve these financial goals. Although student loan stress correlates with the amount of debt, low income seems to contribute more to student loan default than high debt.

Findings:

- When student loan debt exceeds annual income after graduation, college graduates are twice as likely to delay getting married, having children and buying a home.

- College graduates who said that their undergraduate education was worth the cost tend to have much higher annual income and much lower undergraduate debt than college graduates who feel that their education was not worth the cost.

- Student loan defaults seem to depend more on low income than on high debt.

- We don’t really have a student loan problem so much as a college completion problem. College dropouts are four times more likely to default on their student loans than college graduates, and represent two-thirds of the defaults.

- Student loan stress increases as the amount of student loan debt increases. Students who graduate with $100,000 or more in student loan debt are almost twice as likely to report high or very high stress from education-related debt as compared with students who graduate with $25,000 or less in student loan debt (65% vs. 34%).

Delays in Achieving Major Financial Goals

An analysis of data from the recently released 2012 follow-up to the 2008 Baccalaureate & Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B:08/12) demonstrates that student debt can cause delays in major financial goals even four years after graduation.

This table shows the impact of a high student debt-to-income ratio on major financial goals. The likelihood of each negative outcome is double for Bachelor’s degree recipients with a student debt-to-income ratio of 1:1 or more as compared with college graduates who have no debt. A student debt-to-income ratio greater than 1:1 can be a sign of excessive student debt.

Impact of Student Debt-to-Income Ratio |

No Debt |

< 25% |

25% to 49% |

50% to 74% |

75% to 99% |

≥ 100% |

Delayed Getting Married |

15% |

18% |

20% |

25% |

29% |

30% |

Delayed Having Children |

21% |

22% |

29% |

32% |

39% |

38% |

Delayed Buying a Home |

26% |

32% |

41% |

49% |

50% |

47% |

Work More than Desired |

23% |

26% |

36% |

42% |

49% |

44% |

Took Job Outside Field |

29% |

29% |

35% |

42% |

48% |

55% |

Took Job Instead of Further Education |

21% |

27% |

33% |

39% |

36% |

37% |

When total student loan debt exceeds annual income, a student debt-to-income ratio of one or more, it will be difficult for the borrower to repay his or her student loans in ten years or less. Instead, they will need alternate repayment plans, such as extended repayment or income-driven repayment, to afford the monthly loan payments. These repayment plans reduce the monthly payments by increasing the term of the loan. This increases the total interest paid over the life of the loan.

Bachelor’s degree recipients with excessive student debt are about twice as likely to delay getting married, having children and buying a home as compared with students who graduate with no debt. They are also twice as likely to work more than desired, take a job outside their field and to take a job instead of enrolling in further education.

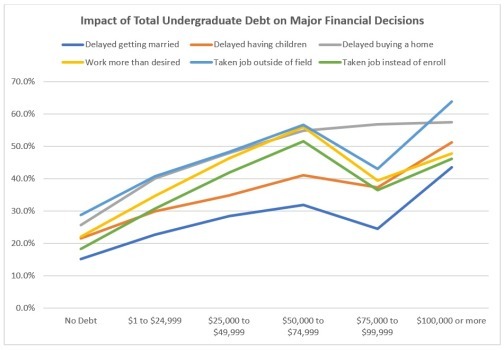

This chart shows the impact of total undergraduate student loan debt on major financial goals. It shows similar results to the data on student debt-to-income ratios, but there is a curious dip in the chart at $75,000 to $99,999 in total student loan debt. This is at about the 99th percentile for undergraduate debt.

The increased volatility in the chart at the point of the dip may be due to a smaller sample size at that debt level. It could also be due to borrowers with extreme debt being more likely to choose alternate repayment plans, such as extended repayment and income-driven repayment, than can cut the monthly payment in half or more.

Note that this data is for college graduates who received a Bachelor’s degree. It does not include data for Associate’s degree and Certificate recipients, nor recipients of more advanced degrees. It also does not include data on college dropouts.

Borrowers who delay getting married, having children and buying a home have student debt at graduation that is $3,527, $3,736 and $4,333 higher, respectively, than borrowers who don’t delay these life cycle goals. These borrowers have monthly loan payments that are $37, $65 and $44 higher, respectively. It is surprising that such a small difference in the amount of debt or student loan payments would cause delays in these events.

However, the delays may be due to these borrowers having lower income, not higher debt, causing the monthly student loan payments to represent a greater percentage of monthly income. Borrowers who delay getting married, having children and buying a home have an annualized total salary for all jobs in 2012 that is $7,928, $8,506 and $8,549 lower, respectively. The difference in income is much greater than the difference in loan payments.

Impact of Debt and Income on Default

Among students who graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in 2007-08, students who default have a lower monthly student loan payment in 2012 than students who don’t default ($280 vs. $348) despite higher outstanding student loan debt ($30,088 vs. $24,929), but the loan payments represent a greater percentage of income (35% vs. 26%).

The annualized total salary from all jobs in 2012 was $7,673 lower among college graduates who were in default on a federal loan as of 2012, as compared with college graduates who were not in default.

This suggests that the income after graduation may have a greater impact on the repayment trajectory of Bachelor’s degree recipients than the debt at graduation. Efforts to increase the income of college graduates may have a greater impact on reducing default rates than efforts to reduce student loan debt.

Was College Worth the Cost?

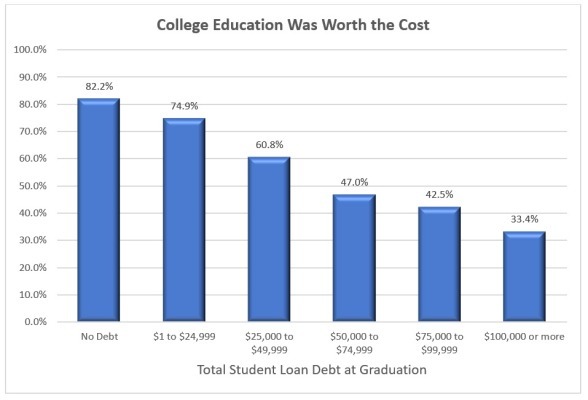

As the total amount borrowed for the student’s college education increases, fewer Bachelor’s degree recipients say that their college education was worth the financial cost. Four-fifths (82%) of Bachelor’s degree recipients with no debt say that their education was worth the cost, compared with a third (33%) of college graduates with $100,000 or more in student loan debt.

This chart shows that satisfaction with the return on the student’s college investment decreases monotonically as student loan debt increases.

A similar result shows that fewer Bachelor’s degree recipients feel that their education was worth the cost as the monthly loan payment increases as a percentage of income. While three quarters of borrowers with a debt-service-to-income ratio of up to 10% feel that college was worth the cost, that decreases to 57% for borrowers whose student loan payments represent more than a fifth of income.

College graduates who said that their undergraduate education was worth the cost, as of 2012, had an annualized total salary from all jobs that was $10,179 higher and cumulative undergraduate student loan debt that is $8,843 lower. Thus, higher income and lower debt may contribute to a positive feeling as to whether college was worth the cost.

College Dropouts are More Likely to Default

We don’t have a student loan problem, at least not yet, so much as a college completion problem.

Based on data from the 2009 follow-up to the 2003-04 Beginning Postsecondary Students longitudinal study (BPS:04/09), college dropouts are 4.2 times more likely to default on their student loans than college graduates, and represent two-thirds (63%) of the defaults. They have the debt, but not the degree that can help them repay the debt.

Among students who initially enroll in a Bachelor’s degree program before eventually attaining a Bachelor’s degree, college dropouts are 34.6 times more likely to default than Bachelor’s degree recipients and represent 82% of the defaults.

The parents’ highest education level also has a big impact on default rates. First-generation college students – students who are first in their families to go to college – are 2.7 times more likely to default as compared with students whose parent has at least a Bachelor’s degree and they represent 80% of the defaults.

Student Loan Stress

Financial difficulty is a great source of stress for student loan borrowers. More than two-fifths (41%) of Bachelor’s degree recipients report high or very high stress from education-related debt, based on data from B&B:08/12. A third (34%) of students graduating with less than $25,000 in student loan debt report high or very high stress, compared with two-thirds (65%) of students graduating with $100,000 or more in student loan debt.

Student loan stress is often caused by a lack of understanding of student loan debt, which leads to a lack of control over the debt. You can reduce student loan stress by learning about financial literacy, keeping track of student loan details and other spending, automating student loan payments and accelerating repayment of high-interest debt.